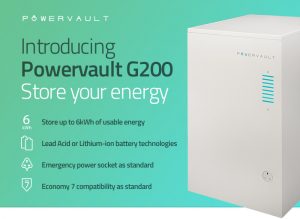

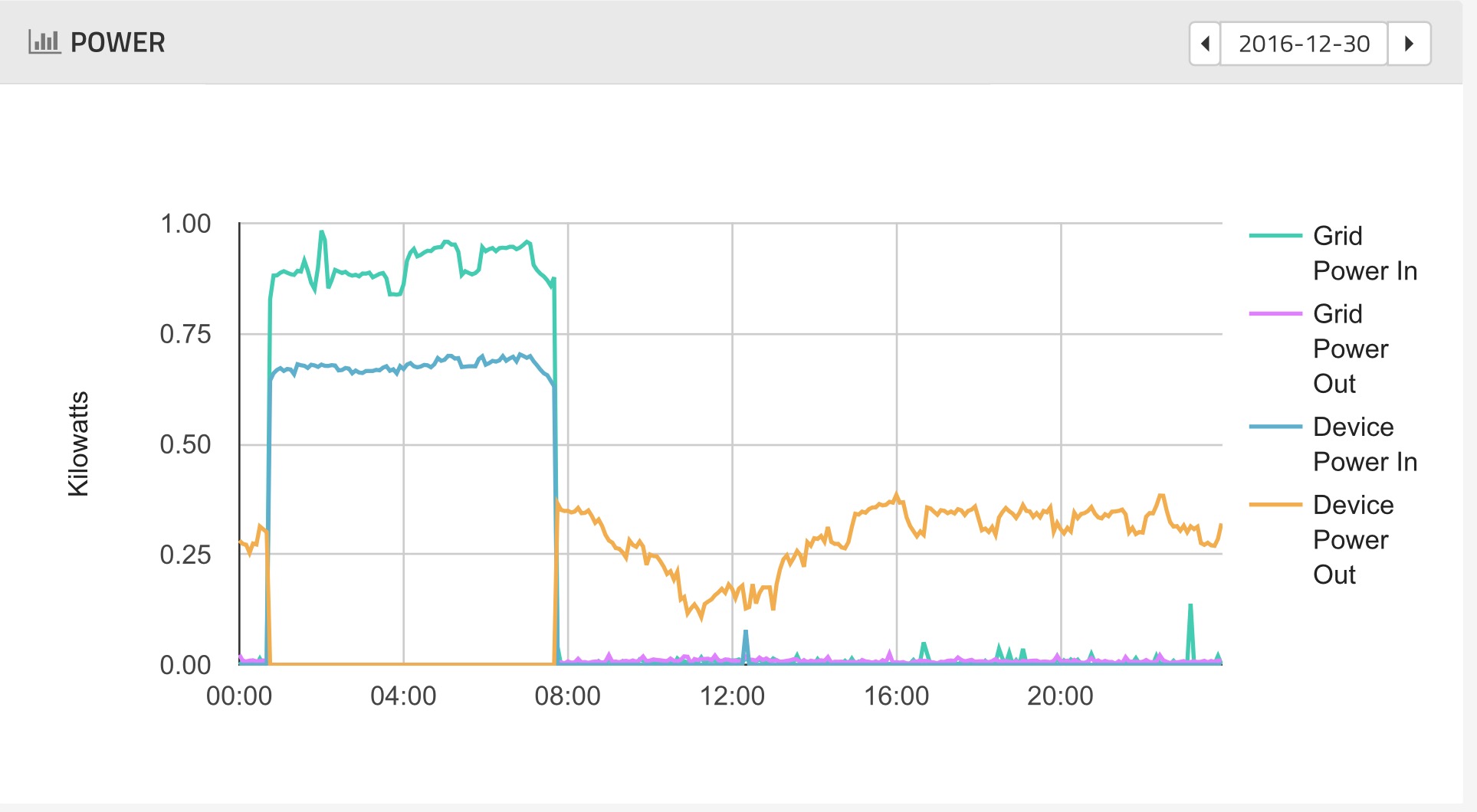

Today I’ve been thinking about configuring the Powevault storage system around my smart electricity tariff in which costs can vary every half hour.

Today I’ve been thinking about configuring the Powevault storage system around my smart electricity tariff in which costs can vary every half hour.

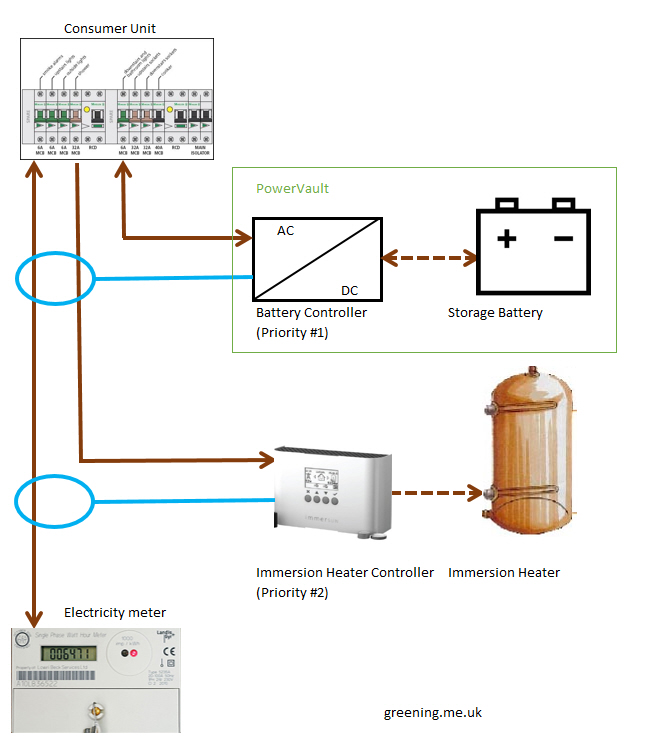

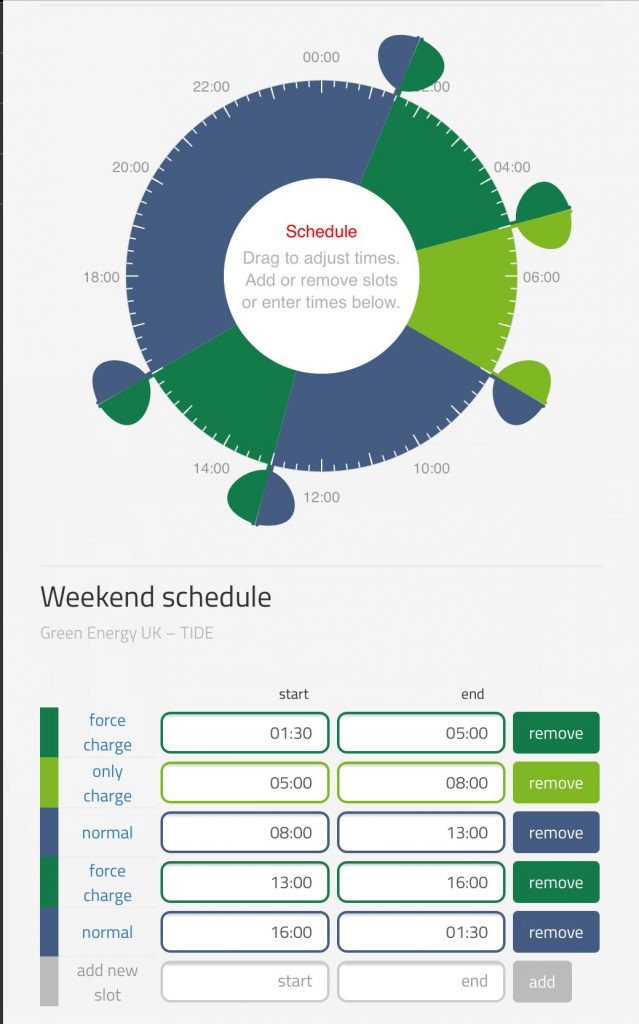

My battery has an ability to be configured around a tariff called TIDE. I don’t have TIDE, but the ability to configure around TIDE can be reused for my tariff. The unit can be configured using a table or the clock as illustrated. There are several sections:

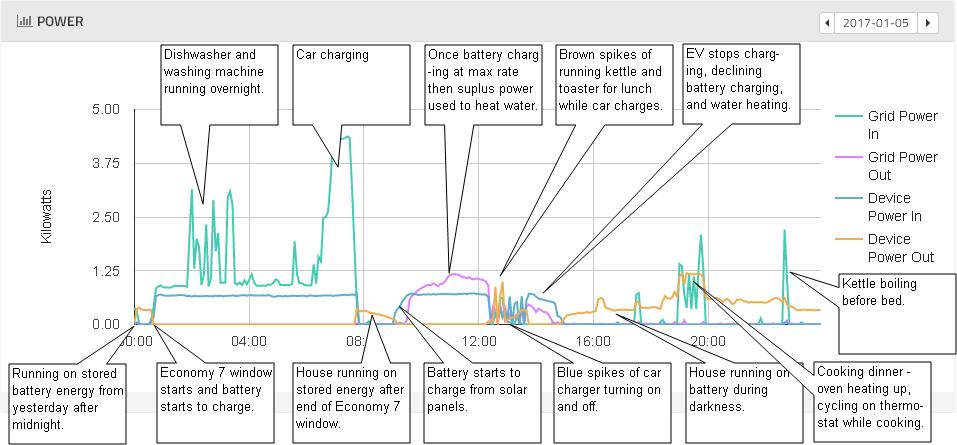

- Force charge – the battery storage charges at its maximum power (only 800 Watts) for 3.5 hours while electricity is cheapest.

- Charge only – a period while electricity is not quite so cheap when the battery will charge proportionally to any solar surplus, but will not discharge. It wouldn’t make sense to start discharging the battery when electricity is only marginally more expensive than when the battery was charged. This also prevents the battery discharging into my electric car if the car charges for a longer period than the battery.

- Normal – storage system will either charge proportionally to solar surplus, or discharge to minimise input.

- Force charge – as previously charges at maximum power in this case to ensure that some power is stored prior to the most expensive period.

- Normal – as previously but intended to cover the peak rate 4:00 to 7:00 PM period and beyond if there’s still stored energy.

Now that this pattern has been created, it can be adjusted by dragging the tabs around clock to adjust for when the cheapest power is at a different time day-to-day.

In the longer term I hope to automate such adjustment, although my priority is getting the car charger to automatically operate when power is cheapest.